"I think we may be lucky that insects are too small and remote ever to have entered our understanding in the way that birds and flowers have. If we saw their lives for what they really are I think it might be too much for us to bear."

- The Unofficial Countryside (1973)

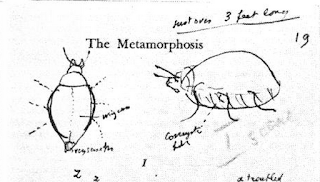

2: The Case of Seth Brundle

If frustrated salesman Gregor Samsa remains concerned about the welfare of others following his metamorphosis, the same cannot be said of eccentric scientist Seth Brundle who, following an experiment, slowly mutates into a human-insect hybrid - the so-called Brundlefly - a creature monstrous of face, monstrous of soul.

That is to say, a devil harbouring within himself all the vices and base appetites of one whose very ugliness is the expression of a development that has been thwarted by crossing (as Nietzsche says of Socrates).

In short, the Brundlefly is a creature of instinctual malice, cf. the Samsabeetle who was one of kindness and sensitivity despite his appearance. On the plus side, in the early stages of his transformation before he sheds his humanity and all the trappings of such (including teeth, hair and skin), Brundle does enjoy increased strength, stamina, and sexual potency.

Later, he's able to climb the walls and crawl across the ceiling - something that Gregor also enjoys doing. And if no longer able to eat solid food, Brundle gains the astonishing - if repulsive - ability to dissolve his meals by vomiting digestive enzymes onto them (an ability which, as we see later in the film, can also serve as a corrosive form of self-defence).

Ultimately, if the case of Gregor Samsa makes us sympathetic and sorrowful at his demise, the case of Seth Brundle only makes us afraid. Very afraid. But what is it exactly we fear? The answer, says Cronenberg, is the disease and old age that threaten all of us with a becoming-monstrous; the mortal corruption within rapidly deforming the flesh and destroying our reason.

Just thinking about it is enough to make one weep ninety-six tears ...

Notes

To read part one of this post on becoming-insect, the case of Gregor Samsa, click here.

To listen to a uniquely brilliant take on this question by The Cramps, click here.

That is to say, a devil harbouring within himself all the vices and base appetites of one whose very ugliness is the expression of a development that has been thwarted by crossing (as Nietzsche says of Socrates).

In short, the Brundlefly is a creature of instinctual malice, cf. the Samsabeetle who was one of kindness and sensitivity despite his appearance. On the plus side, in the early stages of his transformation before he sheds his humanity and all the trappings of such (including teeth, hair and skin), Brundle does enjoy increased strength, stamina, and sexual potency.

Later, he's able to climb the walls and crawl across the ceiling - something that Gregor also enjoys doing. And if no longer able to eat solid food, Brundle gains the astonishing - if repulsive - ability to dissolve his meals by vomiting digestive enzymes onto them (an ability which, as we see later in the film, can also serve as a corrosive form of self-defence).

Ultimately, if the case of Gregor Samsa makes us sympathetic and sorrowful at his demise, the case of Seth Brundle only makes us afraid. Very afraid. But what is it exactly we fear? The answer, says Cronenberg, is the disease and old age that threaten all of us with a becoming-monstrous; the mortal corruption within rapidly deforming the flesh and destroying our reason.

Just thinking about it is enough to make one weep ninety-six tears ...

Notes

To read part one of this post on becoming-insect, the case of Gregor Samsa, click here.

To listen to a uniquely brilliant take on this question by The Cramps, click here.