I.

Pressed between the 300 or so pages of this book are a series of memories from various contributors who still like to filter their experiences and thinking through the prism of punk in order to explore the past and indicate their own role within it: I was there is the running refrain throughout the work: And bliss it was in that Summer of Hate to be alive (and to be a young punk was very heaven) [a].

There is, of course, a certain irony in this: if punk prided itself on anything, it was the refusal to be nostalgic or to acknowledge that it owed anything to the past: No Elvis, Beatles, or the Rolling Stones in 1977 ... [b]

Similarly, punk was not sentimental. As Tony Drayton reminds us, the phrase Kill Your Pet Puppy meant breaking all ties, committments, and responsibilities; "reject domesticity, keep on moving [...] never look back, leave your family behind" [195] [c].

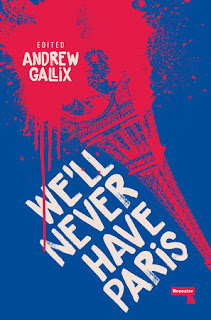

And so there's a further irony in the fact that the book opens with the two editors - Richard Cabut and Andrew Gallix - thanking their partners, parents and children and thereby placing punk within the Oedipal triangle.

Still, never mind the bollocks - let's move on ...

II.

First up, there's a Foreword by Judy Nylon; a colourful figure who, by her own admission, is "often left out of punk histories" [1], despite being - like her friend and compatriot Chrissie Hynde - on the London scene from the very beginning.

I suspect the reason for this is that Nylon is bigger and more complex than any scene or subcultural

identity, which makes her - like many of the singular individuals in this period - too punk for punk. The fact that her "very existence would eventually come into conflict with Malcolm and Vivienne's version of punk" [2] probably also helps to explain her exclusion from many (official) accounts of the period.

Next comes a two part Introduction by the editors ...

Richard Cabut makes the perfectly valid point that punk in the early days - "before the Clash essentialy" [8] - had no fixed essence or political allegiance, but was, rather, a defiant and stylish response to the boredom of everyday life.

Where he and I differ, is that he understands this in terms of a "quest for truth and significance" [9], whilst I see it more as the playful deconstruction of these and related ideals as part of what D. H. Lawrence terms a sane revolution:

If you make a revolution, make it for fun,

don’t make it in ghastly seriousness,

don’t do it in deadly earnest,

do it for fun.

Don’t do it because you hate people,

do it just to spit in their eye. [d]

This resentment-free gobbing - and not the search for meaning - is surely what defines punk, is it not?

Andrew Gallix, meanwhile, muses on the passing of time and the fact that even punk rockers - unless they live fast enough to die young like Sid and Nancy - get old ...

I suspect, however, as a reader of Deleuze, Gallix is perfectly aware of the fact that one can, in fact, age stylishly - that is to say, like Malcolm (but unlike Rotten) - not by attempting to remain young, but by extracting the molecular elements, the forces and flows, that constitute the youth of whatever age one happens to be.

Gallix also warns of the dangers of retrospective reinterpretation; "of the way in which the past is subtly rewritten, every nuance gradually airbrushed out of the picture" [11]. For this is not just a way of negating certain inconvenient elements in the past, but of creating a sanitised present. This whitewashing of history and murder of reality is what Baudrillard terms the perfect crime.

Ultimately, however, the cultural importance of punk must be remembered, even if, as a selective process, remembering always involves a degree of forgetting.

Indeed, Gallix argues that punk must not just be remembered, but commemorated in museums and art galleries; both as "the last great youth subculture" [12] and a "summation of all avant-garde movements of the 20th-century" [12] [e].

III.

In his essay 'The Boy Looked at Eurydice', Gallix continues to reflect upon the punk obsession with youth: "All we can say for sure is that, more than any other subculture before or since, punk was afflicted with Peter Pan syndrome." [17]

That's probably true: I remember one of the first things I ever wrote was entitled Never Trust Anyone Over Twenty and I always (like Sid) used the term grown-up perjoratively. Again, this came from Malcolm who encouraged his spiky-haired charges to be childish, irresponsible and disrespectful of adult authority [f].

More importantly, however, was the fact that punk was a thinking against itself - "internal dissent was its identity" [26]. Real punks, as Gallix rightly says, always hated the term: "Being a true punk was something that could only go without saying, it implied never describing oneself as such" [26-27] [g].

IV.

For me, one of the most interesting pieces in Punk Is Dead is by Tom Vague who retraces the semi-mythical origin of punk rock to the Situationist International and the Gordon Riots of 1780; a connection first made by Fred Vermorel.

The fact is, whilst you can analyse the Sex Pistols from various perspectives, to talk exclusively about the music or the fashion whilst ignoring the politics which inspired McLaren and Jamie Reid is to profoundly miss the point.

Crucial aspects of the project - particularly in the glorious last days of The Great Rock 'n' Roll Swindle, when the band essentially no longer existed - will simply not make sense unless you first understand the political context in which things evolved and I would advise everyone to read Chris Gray's Leaving the Twentieth Century (1974), which, as Vague reminds us, is a kind of blueprint for the punk revolution [h].

V.

Sadly, of course, for the majority of punk rockers it was all about the music (not the chaos); all about forming (or following) bands, making (or buying) records, playing (or going to) gigs, etc. These were the kind of people who read the NME (not Guy Debord) and failed to see that the most exciting thing about Never Mind the Bollocks was the sleeve (just as the only interesting thing about Johnny Rotten was his public image).

Unfortunately, these music lovers abound within the pages of Punk Is Dead - still talking reverently about rock history and referring to the Sex Pistols as the Pistols thereby turning them into just another boring band rather than the embodiment of an attitude and an approach to art, politics, and life that bubbled up at 430 Kings Road.

To his credit, Paul Gorman understands the importance of the above address as an immersive art environment and recognises that the music was simply an expression of SEX and Seditionaries (and arguably of far less importance than McLaren and Westwood's clothes designs) [i]. Not everyone could join the band - but anyone could be a SEX Pistol if they had the right look, the right attitude.

Punk was perhaps not all and always about Talcy Malcy, but, as Gorman says, without McLaren and his odd little shop at 430 Kings Road, punk "wouldn't have taken the form it did" [77] [j].

VI.

I would normally at this point in a review indicate which are the pieces (and who are the authors) contained in this collection that I really hate - and there are several (not to mention one or two essays that simply don't belong in this book, interesting as they may be).

But, in the spirit of Richard Cabut's

positive punk, let me end with a wonderful line taken from Dorothy Max Prior's 'SEX in the City', an amusing account of her days working as a stripper in the pubs of punk London, full of dodgy-geezers and brassy-birds:

"Modernity killed not only every night, but every lunchtime over a pint of Double Diamond in a City Road boozer." [118]

Notes

[a] This line from Wordsworth - paraphrased here - is also paraphrased by Andrew Gallix in 'The Boy Looked at Eurydice', in Punk Is Dead, (Zero Books, 2017), pp. 17-18. Note that future page references to this book will be given directly in the text.

To his credit, punk-turned philosopher Simon Critchley says he consciously tries not to lecture young people about "how great it was to be alive in the 1970s". Of course, as he admits, he often fails in this. See 'Rummaging in the Ashes: An Interview with Simon Critchley', Punk Is Dead, p. 39.

[b] As the Clash sang on the B-side of their first single White Riot (CBS, 1977): click here. Andrew Gallix, however, persuasively argues that without nostalgia we would have no Homer or Proust. See his Introduction to Punk Is Dead, p. 12.

See also 'Rummaging in the Ashes: An Interview with Simon Critchley', in which the latter says that although he hates nostalgia, "it is unavoidable and I get whimsical when I think back to the punk years and how everything suddeny became possible". Punk Is Dead, p. 37.

[c] Tony Drayton (in conversation with Richard Cabut), 'Learning to Fight', Punk Is Dead. Drayton was the founder of the punk fanzines Ripped & Torn (1976) and Kill Your Pet Puppy (1980).

[d] D. H. Lawrence, 'A sane revolution', The Poems Vol. I, ed. Christopher Pollnitz, (Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 449.

[e] Interestingly, Simon Critchley takes an entirely opposite view: "I must say that I find the idea of the commemoration of punk particularly distasteful, and that punk can be archived and celebrated in museums pretty awful." See 'Rummaging in the Ashes: An Interview with Simon Critchley', in Punk Is Dead, p. 38.

[f] Ted Polhemus picks up on the deliberate and determined childishness of punk in his essay 'Boom!', describing it as "the opposite of the beard-stroking, educated, technically-accomplished, grown-up world where the Boring Old Farts had reduced the anything-goes spirit of rock 'n' roll to a limp, ageing shadow of its former self". See Punk Is Dead, p. 98.

[g] As Paul Gorman writes in 'The Flyaway-Collared Shirt': "Everyone I knew, and/or admired, moved on from punk as soon as it was given a name. [...] The richness of [the] scene had been traduced to the saleable gob 'n' pogo archetype: spiky hair, permanent sneer, brotel creepers, Lewis leathers." See Punk Is Dead, p. 105.

[h] For example, Chris Gray's idea of forming a totally unpleasant pop group "designed to subvert show business from within would obviously be a major influence on the [Sex] Pistols project". See Andrew Gallix, 'Unheard Melodies', Punk Is Dead, p. 213.

[i] As Richard Cabut says in 'A Letter to Jordan', in terms of cultural influence upon style, SEX (later to become Seditionaries and World's End) is "the most influential shop/meeting place ever". See Punk Is Dead, p. 120. Cabut is also right to recognise - like Adam Ant before him - that the perfect embodiment of SEX was Jordan, rather than Rotten.

[j] Ted Polhemus challenges the view that punk was primarily and most significantly shaped by Malcolm:

"Not only is this view a reductionist distortion of how history happens - and actually did happen in 1976 - but it also fails to give credit were credit is surely due to the startling, unprecedented creativity of hundreds and then thousands of teenagers like John Lydon [...] and so very many others whose contribution was great but whose names were never known to us [...]."

See his essay 'Boom!' in Punk Is Dead, p. 99. The fact that Polhemus refers to Rotten as John Lydon perhaps indicates where his sympathies lie and why he might wish to down play McLaren's role.