I.

Although D. H. Lawrence's Australian novel, Kangaroo (1923), is little remembered today outside of certain red-bearded circles, it was critically well-received at the time (perhaps less for its philosophy and more for its descriptions of the bush).

One of the things I admire about it, however, is Lawrence's use of actual text drawn from a popular weekly news magazine; namely, the Sydney Bulletin - "the only periodical in the world that really amused" [b] the novel's protagonist Richard Somers:

"The horrible stuffiness of English newspapers he could not stand: they had the same effect on him as fish-balls in a restaurant, loathsome stuffy fare. [...] But the Bully, even if it was made up all of bits, and had neither head nor tail nor feet nor wings, was still a lively creature. He liked its straightforwardness [...] It beat no solemn drums. It had no deadly earnestness. It was just stoical, and spitefully humorous." [269].

Whether we might find the same "laconic courage of experience" [272] in today's edition of the Metro [c] - copies of which are sitting in a pile at the front of the bus - is extremely doubtful I fear ...

II.

And, having now flicked through the paper in search of some entertaining snippets - or bits as Lawrence calls the short news items that catch his eye [d] - I can confirm that the Metro is completely devoid of momentaneous life or even vaguely interesting anecdotage, with the single exception being the story of a rat-catcher from Wakefield who recalled once having a client who had a rat living in the wooden slats of his bed and another who was left screaming when she discovered a rat floating in her toilet bowl (only after having already sat down to urinate) [e].

Having said that, I was sorry to read that a fluffy tortoise-shell cat named Rosie - believed to be the world's oldest, aged 33, and living in Norwich with her human companion Lila Brissett - has just died [f].

And I would like to send congratulations to a couple in Crewe - Peter and Peggie Taylor - who have been married for 78 years and who have both now celebrated their 100th birthdays [g].

Notes

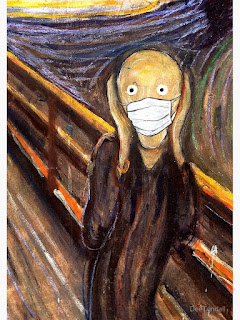

[a] Known as the 'bushman's bible', The Bulletin was an Australian weekly magazine based in Sydney and first published in 1880. It featured articles on politics, business, poetry, fiction and humour and exerted significant influence on Australian society and culture, promoting the idea of a national identity distinct from its British colonial origins. The copy shown here, dated 10 August 1922, may have been read by D. H. Lawrence, as he was in Sydney on this date, before departing for San Francisco on the 11th. Readers who are interested, can read this edition of The Bulletin online thanks to the National Library of Australia: click here.

[b] D. H. Lawrence, Kangaroo, ed. Bruce Steele (Cambridge University Press, 1994), p. 269. Future page references to this work will be given directly in the post.

As Bruce Steele notes in his Introduction to Kangaroo, Lawrence's use of the Bulletin "was not simply as a quarry for verbatim quotation [...] Sometimes he adapted or extrapolated from it [...] He even attributed ideas and views to it" [xxxiv].

Arguably, Lawrence's use of a print publication was the most radical and imaginative since Picasso cut and pasted a piece of Le Journal into his collage Guitar, Sheet Music and Wine Glass (1912); a work widely regarded as the first self-consciously modern artwork to incoporate real newsprint. As Steele concludes, Lawrence seems to have not only been amused by the Bulletin - including its cartoons and advertisements - but found it a "productive source of idiom as of fact" [xxxv], giving a certain authenticity to his novel.

Finally, readers might also be reminded that earlier in chapter VIII of Kangaroo Lawrence incorporates an "almost thrilling bit of journalism" [168] by A. Meston from the Sydney Daily Telegraph virtually in full - something dismissed as padding by critics of the novel. Such criticism, however, is dealt with by John B. Humma in his excellent reading (and defence) of Kangaroo. See 'Of Bits, Beasts, and Bush: The Interior Wilderness in D. H. Lawrence's Kangaroo', in South Atlantic Review, Vol. 51, No. 1 (Jan., 1986), pp. 83-100. Click here to read on JSTOR.

[c] The Metro is the highest-circulation freesheet tabloid newspaper in the UK. It is published in tabloid format by DMG Media and distributed on weekdays.

[d] The bits that most fascinated Lawrence were actually contributions from readers of the Bulletin published on a page known as 'Aboriginalities'.

[e] Danny Rigg reports on the work of professional rat-catcher Keiran Sampler (and his two canine assistants Poppy and Panny) in a story entitled 'It's rat-a-pooy', in today's Metro (16 September, 2024), p.7. Click here to read the story in the e-edition.

[f] See 'Rest in puss Rosie ... Oldest cat in world dies aged 33', in the Metro (16 September, 2024), p. 9. Click here to read the story in the e-edition.

[g] See Izzy Hawksworth, 'We're both 100 years old and still married after meeting in a bar', in the Metro (16 September, 2024), p. 9. Click here to read the story in the e-edition.