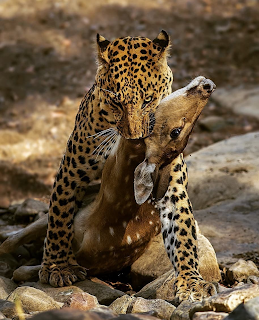

Front cover of Lady Chatterley's Daughter

by Patricia Robins (Consul Books, 1961) [a]

I.

D. H. Lawrence's final and most notorious novel, Lady Chatterley's Lover (1928), has been a gift that keeps on giving to parodists and pornographers, as well as more earnest filmmakers and writers of popular romantic fiction, such as Patricia Robins, author of over 80 novels between 1934 and 2016, including, in 1961, a sequel (of sorts) to Lawrence's banned book.

Readers familiar with Lawrence's novel will know that it ends (a little droopingly) with the lovers separated; Connie goes with her sister, Hilda, to their parental home in Scotland and Mellors gets a job on a farm in the Amber Valley district of Derbyshire.

It's agreed that they'll remain apart for six months, so that he can get his divorce (regardless of whether Connie obtains hers from Clifford or not), then reunite in the late spring and buy a small place of their own. By then, their baby will have been born - assuming Connie doesn't miscarry, or decide to have an abortion and forget all about a man who regards their child as a side issue.

The point is, that not only does Robins presuppose that Connie and Mellors do, in fact, reunite, but that the baby is born - and is female. Lawrence gives us the hope of such a happy-ever-after ending, but does not provide such and I think it important to note this before we begin.

II. Chapters 1-3

Set twenty years after Lawrence's novel, in wartime London, Lady Chatterley's Daughter is the tale of a

nurse, Clare Mellors, and the guilty secret which held her on the edge of a surging passion.

Clare is engaged to a young officer called Robin. Whilst he's fighting with Monty and the boys in Tripoli, Clare is living with her aunt Hilda (and cousin Pip) in a flat near Sloane Square. She's a friendly and attractive young woman: "Her figure was perfect and her colouring - the red hair, milk-white skin and very large blue eyes - made her very striking." [7]

But she is withdrawn, even, we might say, a little cold; "there was always an invisible barrier between herself and the opposite sex" [8]. Luckily, her fiancé "seemed to understand and appreciate the quality of reserve in her" [8]. Indeed, he respected her modesty so much that he hadn't attempted to initiate pre-marital sexual relations - which she considered improper - with any real determination.

Clare, then, is the very opposite of her mother, Connie, who had indulged in love affairs both before and after her marriage to Clifford without any sense of shame or wrongdoing, as discussed in a recent post: click

here.

Indeed, Clare is somewhat estranged from both her parents:

"There weren't often rows [...] but undercurrents of dissension and misunderstanding which were turning Clare against her parents and making her less inclined to go home [...] Aunt Hilda seemed to understand her much better than her mother did." [8]

That, I think, is a nice touch by Robins, who appreciates that a couple such as Connie and Mellors, who only ever think of their own fulfilment, would probably have had little time for poor Clare. And I rather like the fact that their daughter is determined to lead a morally conventional lifestyle, upholding traditional ideas to do with sex and marriage and wearing warm and sensible pyjamas to bed.

One day, Robin arrives on leave. It turns out her fiancé is rather like Clifford; fair-haired, good-looking, well-mannered, full of charm and always smartly dressed: "One never associated him with untidy clothes - or untidy principles." [16]

Unfortunately for Clare, war can change a man: as can too much champagne. And after dancing the night away at the Savoy, they return to the flat in Chelsea, where he attempts to seduce her, much to her chagrin:

"She thought she would die of disappointment. She had counted on his integrity and understanding of her feelings. [...] Now, suddenly, Robin was not only completely disregarding the conventions he approved of but was showing a side of his nature she had never seen before." [25]

She asks him to stop and return to his bedroom. But he doesn't: "He was no longer the chivalrous and noble Robin but a stranger who disgusted her." [26] In a frenzy, she finally manages to fight off her fiancé-turned-would-be-rapist. Whilst Clare is understandably upset, Robin is indignant and tells her that if she is so repulsed by sex then she should inform him now: "'I don't want a frigid wife who gives her body as a duty [...]'" [26]

Clare calls him an animal - and hands back her engagement ring. Robin leaves, "nursing his frustrated passions" [28] - which I take to be a euphemism for epididymal hypertension - and ends up in a basement night club in Knightsbridge, where he bumps into an old pal from Nottingham to whom he blurts out his troubles and expresses disbelief that the daughter of the scandalous Lady Chatterley could be so sexually unresponsive.

III. Chapter 4-7

Clare decides to go home for a week; to the beautiful old Sussex farmhouse, just outside Brighton, where her parents had settled and raised her.

Her mother, who is now a plump figure in her forties, had made the house "warm, homely, and comfortable" [33] with thick carpets and curtains; she had even installed central heating (one can't imagine Mellors approving of this, but I suspect he spent most of his time outdoors with his prize herd of cattle).

Clare tells her mother what happened between her and Robin ...

On the one hand, Connie is pleased that the latter is out of the picture, as she and Mellors had never considered him a real man: "Oh, so charming, and English, and well-bred, but too conventional for words" [37]. But, on the other hand, she thinks Clare is being terribly unreasonable and ought to "'forgive the poor boy'" [40].

And with that, Connie returns to stuffing a chicken; proud of her own moral unconventionality. Unfortunately, Clare's father isn't any more understanding:

"Queer that a child of his shouldn't feel the body's urge. Pity if some chap couldn't wake her up. [...] A woman without love and loving must be miserable [...] half-fulfilled, ever-seeking to solve the unknown mysteries of life." [44]

It's depressing to discover that - twenty years on - Mellors is still subscribing to the same cod philosophy. But, alas, all too believable. Rather less believable is the fact that two days after breaking things off with Robin, Clare is canoodling with a tall, slim-hipped, dark-haired American airman from Virginia called Hamilton Craig: "Perhaps Ham would help to lay Robin's ghost completely." [52]

And so she let's him cop a feel of her "rounded little breasts" [53], beneath her pale green woolly jumper. I mean, a gal's got to move on, but this seems a bit hasty and out of character. That said, the minute he tries to raise the stakes, she's playing the virgin card once again and that's the end of their brief romance.

Next up, is Bill Roberts; a handsome naval officer. They have fun together, but in a purely platonic manner. For Bill is engaged to another and so "did not attempt to become either serious or intimate" [69], much to Clare's relief; "it was good to know that she could actually enjoy this sort of thing and feel light-hearted and wthout the old burden of fears and repressions" [70].

This last line makes one wonder if, actually, there is something wrong with Clare; had she had some terrible childhood trauma involving sexual abuse? Or was it the shame she felt at having been born out of wedlock?

If I'd written the novel, I would've opted for the former explanation and revealed Oliver Mellors as an incestuous paedophile à la Eric Gill [b]. But it seems that Robins prefers the latter, telling us how, aged fourteen, Clare was horrified when she discovered her illegitimacy and "the facts about her mother's sensational love-affair with her father" [71].

Rightly or wrongly, Clare felt herself the product of sin - and this is why she has been reluctant to love. And this is why she decided to devote herself to nursing in an attempt to atone for her parents adultery. Again, rightly or wrongly, the shame had stayed with her ever since:

"Even now in the middle of the war, when she was an adult and a nurse, and such things as illegitimacy seemed less terrible, her abhorrence of the whole situation remained." [76]

IV. Chapters 8-11

On another visit to her parents, Clare finally gets to meet her half-sister (i.e., the daughter born to Mellors and his first wife, Bertha), about whom she has almost no knowledge or memory:

"She had a rather curious figure, short, dumpy, with a shabby duffle-coat stretched around a large stomach. She was hatless, with short, lanky hair falling in crimped waves on either side of a long, narrow face. Definitely an unhealthy and unattractive looking person, Clare thought, judging her to be in her early thirties." [82]

Having said that, the woman had a queer wild attraction and brilliant blue eyes. And, it became clear, she wasn't fat, but heavily pregnant. She has come to see Mr. Mellors; so Clare invites her in to await his return.

As the stranger sits drinking a drop of brandy, Clare takes the opportunity to pass further silent judgement upon her; noticing the ladders in her cheap silk stockings, for example, and the awful earrings that make her look like a poorly educated gipsy. Apparently, such snobbery laced with racism was acceptable at the time, but it doesn't help contemporary readers to much like Miss Mellors.

It turns out she - Oliver's eldest daughter (now going by the name Gloria) - had become involved with an American serviceman, who had been "generous with the dollars, nylons, chocolates and cigarettes" [85]. Generous too with his affections, leaving her knocked up, before getting himself posted elsewhere.

Eventually, the woman reveals her identity: "Clare stood perfectly still. It was as though she had been struck by lightning. She went deadly pale." [86] Strangely enough, when Mellors gets home and is confronted by his first child, he too turns pale (maybe it's a family thing).

As for Connie, she reacts rather like Clare at the sight of the wretched figure sat on her sofa, i.e., with cruel judgement and class hatred: "This girl with her dissipated face and dirty nails repelled Connie. [...] She even felt unclean because of the contact with 'Gloria' [...]" [92]

Nevertheless, she abides by her husband's decision to help (and house) the girl in a nearby cottage. And soon enough, she's warming to Gloria and trying to convince Clare not to be so hard on her - an accusation that causes the latter to erupt: "'Why is it that if somebody wants to live decently and stick to their ideals, they are called 'hard'?" [98]

Connie sighs, and decides that her daughter is not only intolerant, but inhuman; whereas Gloria, for all her faults, weaknesses, and vices - in fact, because of these things - is at least human. This doesn't stop Connie walking her daughter to the bus stop, however, when the latter leaves to go back to London.

But Clare, having been called inhuman and an intolerant snob by her mother, is in no mood to reconcile and tells of the great discomfort she felt as a child when her parents paraded naked around the house "preaching the 'Beauties of Nature' [and] giving each other let's-go-to-bed looks'" [101].

In a powerful and moving indictment of her proto-hippie parents, Clare continues:

"'You never have asked yourself what I thought or felt. For instance - if you'd had the smallest understanding, the least you and Father could have done was to reserve exhibiting your great passion for each other until you were in your own bedroom. [...] I suppose you couldn't help it. I've read in books some women are made that way but I think you might have tried a little harder to control yourself in front of me. As for Father, well, the only excuse for him is that he's never known how decent people behave.'" [101-02]

"'If I am a snob, you made me that way. You sent me to the 'best' schools which meant I made friends amongst the 'best' people. How do you think I felt comparing Father with the father of that girl Cynthia who used to be my best friend at school? [...] He was erudite and appreciative of art and music; he could talk about opera, science, history - so many things. How could I ask Cynthia back to our house with you and Father mooning over each other and no other topic of conversation but the birds and the bees.'" [102]

Obviously, this reduces Connie to tears. When she gets home she tells her husband what happened. Mellors tells her to stop fretting and have some tea; his answer - along with fucking - to everything. Strangely, despite feeling heart-sick with a sense of maternal failure, a nice cuppa does the trick:

"Dear Oliver, thought Connie. He was always so kind. This man who had been able to lead her to the ultimate rapture of loving could soothe her just as miraculously." [104]

Thus soothed, Connie learns nothing.

Back at the hospital, it turns out Clare has a friend, Elizabeth Peverel, who "came from a very wealthy family with a big estate up in Derbyshire" [110], only five miles away from Wragby. Liz has even met Sir Clifford, once or twice, whom she describes as a friend of her father's and "'an attractive man in a queer sort of way'" [111].

This serves to further kindle Clare's interest in Sir Clifford, about whom she has been thinking a great deal recently. Chapter ten ends, however, on a rather nasty note: Clare is pestered by phone and letter, before being finally accosted in person, by a former patient who is erotically obsessed with her.

Luckily, before things turn very nasty, she is saved by a passing member of an ambulance crew - a woman with "strong brown attractive hands and [...] rather handsome in a boyish way" [117], called Jo, who invites Clare back to her place for a drink ...

Clare finds Jo to be extremely pleasing company. Despite her masculine appearance "she had a distinctly feminine understanding of what another woman needed" [121] and it was a huge relief for Claire "not to have to be on her guard as was inevitable with a man" [121]. Jo was without doubt a "most unusual, charming woman" [121].

The two women enjoy fish for dinner - served with "one of Jo's wonderful sauces" [125] and a bottle of white wine. Afterwards, Jo made some excellent coffee. Then the sirens sound, announcing another German air raid. Jo insists Clare simply must stay the night at her flat, as the bombs fall all around them.

To her credit, Jo refuses to let the Luftwaffe spoil her evening; she puts on another record and makes some more strong coffee. The two women talk and laugh until long past midnight:

"Clare allowed herself to be completely organized by Jo. She had to admit that Jo seemed to know exactly what she most needed. A hot bath - even a big hot towel, warmed by Jo in front of the fire and tossed to her when she was ready for it. Perfumed essence to make the water especially tempting and fragrant [...] She had put fresh linen on the bed in her little room and in spite of Clare's protests finally tucked her up there. [...]

Clare was a little bewildered by all this attention but grateful. She had never known anybody look after her as well as Jo did." [130]

As she drifts off to sleep, Jo stands looking down at her, admiring her beauty ...

The next morning, Jo leaves for work whilst the objet de son désir makes herself some coffee. Unfortunately, it's at this point that Monica - Jo's ex-girlfriend - turns up and there's a scene. She tells Clare: "'I think you're a bitch, to stay here with Jo, knowing just what she means to me and how things are between her and myself.'" [133]

Still the sexually naive Clare doesn't click what's going on. It's only after Monica screams: "'I loved Jo. And I know she loves me. I won't let you take my place here!'" [134] before collapsing on the sofa in tears that - finally! - the penny drops.

And once the penny has dropped, Clare responds with the same level of hateful prejudice and homophobia that her father displays in a famous rant in

Lady Chatterley's Lover (see chapter XIV or click

here for my discussion of this in a post from June 2013):

"At last she realized what this was all about. She knew what Jo was. One of those. Her attention, the wonderful way she had cherished Clare ... all that thoughtful care, sprang not from the normal desire for friendship but from perversion. [...]

Now that Clare remembered the look in Jo's eyes and the way those long nervous fingers had grasped hers, she shivered [...] She, who had had sex flung at her in its natural form all her life, had never come up against this sort of thing before. It did not hold out a vestige of attraction for her. [...] The very thought of facing Jo again horrified Clare. Better Cas Binelli [ - the former patient from whose clutches Jo had rescued her -] than that." [134-35]

That, for me, is the final straw: having overlooked her ascetic idealism, her judgemental snobbery and casual racism, I cannot simply turn a blind eye to her lesbophobia.

Clare Chatterley may be a good nurse. And she may be very beautiful. But she's a nasty-minded woman; one whom would rather be raped in a back alley by a straight man, than treated with loving kindness by a queer woman. The only positive thing that can be said is that, unlike her father, at least she doesn't think lesbians should be killed.

That is the end of Part One of Robins's novel. My hope is that in Part Two Clare will learn to see things differently ...

Notes

[a] All page references given in the post refer this edition of the text.

[b] Eric Gill (1882-1940) was an English sculptor, designer, and printmaker, associated with the Arts and Crafts movement. He is perhaps best known today however, as an incestuous paedophile, who not only had illicit sexual relations with his sisters and daughters, but also with his dog: click here for further details. Interestingly, in chapter XVII of Lady Chatterley's Lover, Clifford interviews his gamekeeper about the local scandal surrounding him and at one point the ever-impertinent Mellors says: "'Surely you might ma'e a scandal out o' me an' my bitch Flossie. You've missed summat there.'" Which is a strange thing to say and suggests that Mellors must himself at some point have entertained such a zoosexual fantasy.

See D. H. Lawrence, Lady Chatterley's Lover, ed. Michael Squires, (Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 268-69.

To read part two of this post on Lady Chatterley's Daughter, click here.

.jpg)