We will have to ask ourselves the only serious question that truly matters: where are we now?

And it is a question we should answer not just with our words, but with our lives too.

VI.

Another of the great zombie-mantras of the pandemic - again, here in the UK at least - was: Protect the NHS.

Indeed, we were expected not only to protect the National Health Service, but love it and elevate it to the status of a religion.

And so Agamben is right to define medicine as the victorious faith of the 21st-century; a cultic practice that posits health (by which it means bare life) above everything else, turning it into a moral obligation: Thou shalt not be sick!

But the funny thing is, "the medical religion offers no prospect of salvation [...] the recovery to which it aspires can only be temporary, given that the malignant god - the virus - cannot be annihilated once and for all" [53], mutating into variants as it does.

It is thus the task of philosophers to again enter into conflict with religion:

"I do not know if the stakes will be reignited or if there will be a list of prohibited books, but certainly the thought of those who keep seeking the truth and rejecting the dominant lie will [...] be excluded and accused of disseminating fake news [...] As in all moments of real or simulated emergency, we will again see philosopers be slandered by the ignorant, and scoundrels trying to profit from disasters that they themselves have instigated." [54]

Ecrasez l'infâme!

VII.

As readers of Torpedo the Ark will know, I hate Zoom [click here] and I despise the way in which many who should know better - university lecturers, for example - have willingly embraced its use and thus allowed the pandemic to serve as a "pretext for an increasingly pervasive diffusion of digital technologies" [72].

This has not simply transformed teaching, but effectively negated student life as a form of existence that had evolved over centuries:

"Being a student was, first and foremost, a form of life, one to which studying and listening to lectures were certainly fundamental, but to which encountering and constantly exchanging ideas with other scholarii [...] was no less important." [73]

I agree with that.

And I agree with this: those academics who consent to hold all their classes remotely and comply with the new online order, are the "exact equivalent of those university professors who, in 1931, pledged allegiance to the Fascist regime" [74].

Those students who really love student life, will oppose the new techno-barbarism and establish their own circles of learning and friendship.

VIII.

I also agree with Agamben when he writes that the phrase conspiracy theorist - used to discredit those who refuse to accept the official government narrative repeated by the manistream media - "demonstrates a genuinely surprising historical ignorance" [75].

Not everything happens randomly or by chance; sometimes events are planned and coordinated by powerful organisations, groups, or individuals. Dismissing anyone who seeks to explain the pandemic by making reference, for example, to the Wuhan Institute, the World Health Organisation, and the pharmaceutical industry, as a conspiracy theorist, is a sign of idiocy.

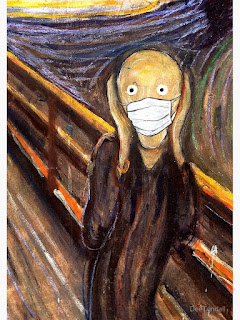

But where I don't agree with Agamben - even though I hate the thought of mandatory masks - is on the question of the face, which he thinks a uniquely human site of truth: "It is in their faces that humans unwillingly drop their guard; it is the face [...] that they express and reveal themselves." [86]

It is precisely this (metaphysical) privileging of the face that I challenge in a post published way back in 2013: click here.

If I refuse to wear a mask across my mouth and nose, it's because, quite simply, I don't wish to restrict my own breathing - and nor do I want to signal my political conformity (and virtue) via a piece of ridiculous theatre.

But it's not because I have a profound human need to recognise myself and be recognised by others - or a desire to communicate my openness.

IX.

In Yōko Ogawa's 1994 sci-fi novel The Memory Police [b], the world is increasingly emptied out as things disappear - including body parts, until, finally, as Byung-Chul Han notes, "there are just disembodied voices aimlessly floating in the air" [c].

I thought of this as I read the following paragraph in Agamben's book, in a section on the importance of physical contact:

"If, as is perversely being attempted today, all contact could be abolished, if everything and everyone could be held at a distance, we would lose not only the experience of other bodies but also, and above all, any immediate experience of ourselves. We would, purely and simply, lose our own flesh." [101]

But then for those who love to Zoom, that's the ideal is it not; to become ghosts in the machine ...?

X.

Last word to Agamben ...

In the Age of Coronavirus, when fear seems to have gripped the hearts of everyone, remember:

"No need to lose our heads, no need to let anyone exercise power on the basis of fear or, by transforming an emergency into a permanent state, to rewrite the rules that guarantee our freedom and determine what we can and cannot do." [95]

Notes

[a] I'm using the English edition of Agamben's Where Are We Now?, trans. Valeria Dani, (ERIS, 2021). All page numbers given in the post refer to this edition.

[b] Yōko Ogawa, The Memory Police, trans. Stephen Snyder, (Vintage, 2020).

[c] Byung-Chul Han, Preface to Non-things, trans. Daniel Steuer, (Polity Press, 2022), p. viii.

To go to Part 1 of this post, click here.