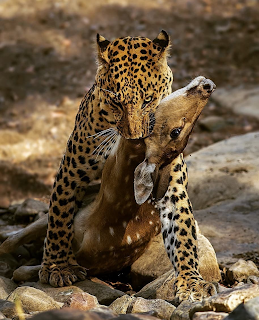

The leopard will never lie down with the antelope.

Whilst the leopard is leopard, he must fall on the antelope, to devour her.

This is his being and his peace, in so far as he has any peace.

And the peace of the antelope is to be devourable.

I.

Those readers familiar with Luc Besson's sci-fi thriller Lucy (2014), starring Scarlett Johansson as a woman who gains superhuman powers - including massively enhanced cognitive abilities - thanks to a (fictional) nootropic (CPH4), will doubtless recall the terrifying opening scene at the hotel when she delivers a metal briefcase to Mr. Jang (a South Korean crime boss played by Choi Min-sik) containing bags of the designer drug in blue-powdered form.

As she waits nervously in the lobby, scenes of a cheetah stalking an antelope flash on the screen, indicating the mortal danger she is in. When she is brought before Jang by his henchmen, she desperately pleads for her life as images of the cheetah having caught its tender young prey, carries it away to be eaten [1].

As a visual metaphor, it's hardly subtle and is perhaps something of a cliché, combining elements of the lurid and the banal that remind one of the kind of pornography that appeals to those men who enjoy the thought of commiting acts of savage sexual violence against vulnerable-looking doe-eyed girls, or to those who desire to swallow others, or fantasise about being devoured by a large predator, red in tooth and claw.

II.

The scene also reminds me, however, of a memorable passage in D. H. Lawrence's essay 'The Reality of Peace', that I'd like to share with readers:

"Look at the doe of the fallow deer as she turns back her eyes in apprehension. What does she ask for, what is her helpless passion? Some unutterable thrill in her waits with unbearable acuteness for the leap of the mottled leopard. Not of the conjunction with the hart is she consummated, but of the exquisite laceration of fear, as the leopard springs upon her loins, and his claws strike in, and he dips his mouth in her. This is the white-hot pitch of her helpless desire. She cannot save herself. Her moment of frenzied fulfilment is the moment when she is torn and scattered beneath the paws of the leopard, like a quenched fire scattered into the darkness. Nothing can alter it. This is the extremity of her desire, this desire for the fearful fury of the brand upon her. She is balanced over at the extreme edge of submission, balanced against the bright beam of the leopard like a shadow against him." [2]

For Lawrence, these two types of animal - predator and prey - exist by virtue of juxtaposition; to negate the being of one would be to negate the being of the other. Similarly, any ideal attempt to reconcile the cat and the rat, the wolf and the lamb, or the leopard and the antelope, "is only to bring about their nullification" [3].

That's arguably true, but what's interesting is how Lawrence eroticises his philosophy - and does so in a manner that many commentators also find porno-lurid and clichéd.

Michael Black, for example, notes how, in the above passage, the deer is female and the leopard male and he wonders what this tells us about Lawrence's sexual politics. It is one thing, writes Black, "to contemplate predation

as a fact of nature; it is another to elevate it to a mystic principle" [4] which eroticises violent death and being devoured.

He has a point, but I suspect Black fails to appreciate just how perverse Lawrence's writing is.

For despite Lawrence's sexual politics mostly oscillating between the romantic and the reactionary, his work also provides us with an explicit A-Z of paraphilias and fetishistic behaviours, obliging readers to think about subjects including: adultery, anal sex, autogynephilia, cross-dressing, dendrophilia, female orgasm, floraphilia, gang rape, garment fetishism, homosexuality, lesbianism, masturbation, naked wrestling, objectum-sexuality, podophilia, pornography, psychosexual infantalism, sadomasochism, and zoophilia. [5]

It's neither shocking nor suprising, therefore, that Lawrence should also allow an element of vorarephilia to enter his text ...

Notes

[1] This scene can be watched on YouTube thanks to Universal Pictures All-Access: click here.

[2] D. H. Lawrence, 'The Reality of Peace', in Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine and Other Essays, ed. Michael Herbert, (Cambridge University Press, 1988), p. 50.

[3] Ibid.

I discussed Lawrence's philosophy of anatgonistic opposition - or what he likes to call polarity - at greater length with reference to 'The Reality of Peace' in an earlier (related) post: click here.

[4] Michael Black, D. H. Lawrence: The Early Philosophical Works,

(Cambridge University Press, 1992), p. 440.

[5] I'm quoting from my post on Torpedo the Ark entitled 'D. H. Lawrence: Priest of Kink' (19 July 2018): click here.