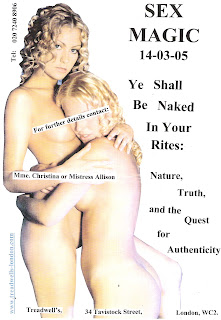

The original poster for the fifth paper in the

I. Opening Remarks

For this third entry in the gymnosophy series of posts, I thought it would be nice to (re-)examine the role of nudity played within modern pagan witchcraft - and to do so by offering an edited version of a paper first given at London's finest occult bookstore, Treadwell's, way back in March 2005.*

The essential argument of the paper was that truth doesn't, in fact, love to go naked - despite what many witches insist on believing, and that there is nothing natural or authentic about nudity. Indeed, working skyclad, very often exposes more than the flesh; not least a lack of style which, like culture, is ultimately founded upon cloth.

Having said that, ritualised nudity as practiced within Wicca isn't simply a naive exhibitionism. It is, rather, a symbolic gesture rich in philosophical and political meaning, involving as it does questions to do with power, freedom, and the body. Whatever it might signify, taking your underwear off in a public space is never simply an innocent act.

II. Five Good Reasons to Get Naked According to A Witches' Bible

The Wiccan penchant for performing ceremonies naked is often justified on the grounds that it's an ancient pagan practice. However, whilst it is certainly the case that ritual nudity does have a long tradition within magic, it should be noted that it was extremely rare within a religious context until it was assigned as a central feature of the witches' sabbat by Christian writers keen to imagine all manner of transgressive activity taking place within the woods at night.

According to Janet and Stewart Farrar, however, this doesn't really matter - "whether or not the widespread Wiccan habit of working skyclad is mainly a phenomenon of the twentieth century revival […] or the continuation of a secret custom […] is hardly important […] what matters is its validity for witches today" - and there are, they claim, at least five good reasons for working naked:

The first is that it challenges the metaphysical division between mind and body. In other words, by working naked and affirming the beauty and potency of the flesh, witches are making a quasi-deconstructive gesture.

Whilst I'd probably not describe this mind/body division as the cardinal sin of the patriarchal period, I’d agree, as a Lawrentian, that it has been modern man's fate to be self-divided in this manner, so that the upper centres of consciousness dominate and exploit the lower centres of sensual and intuitive feeling. I'd also support any attempt to counter this which values nakedness as something positive and pristine and helps us overcome the bad conscience that has attached itself to the body and its forces and flows.

Secondly, according to the Farrar's, a naked body is far more sensitive and responsive than a clothed one and trying to work magic whilst dressed is "like trying to play the piano in gloves". There is, therefore, a sound practical reason to disrobe.

Unfortunately, never having attempted to raise psychic energy whilst naked - nor play the piano whilst wearing gloves - I cannot personally vouch for this. Neither can I confirm or deny their additional claim that "the naked body gives off pheromones far more quickly and efficiently than a clothed one, so it may well be that [...] a skyclad coven is exchanging unconscious information more effectively than a robed one", though this seems reasonable (if, that is, human pheromones actually exist).

The third reason for working skyclad, say the Farrar's, is because it allows one to be oneself.

This psychological claim leaves me profoundly depressed: to suggest that undressing is a "powerful gesture of image-shedding, a symbolic milestone on the road to self-realization" reveals naivety at almost every conceivable level. The Farrar's also assert that when naked we are able to see others for what they really are and to relate at a truer level; one that is entirely unmediated and closer to universal nature.

Of course, they are not alone in believing such nonsense. Indeed, the idea of nudity as a way to reach (and/or liberate) an essential self regarded as the origin of all truth and goodness, is common within Western culture. Our society is filled to bursting with intellectually challenged and emotionally disturbed people striving to achieve authenticity and to create identities in which their deepest selves are expressed.

The fourth reason for witches to get naked is a political consequence of the above. Subscribing as they do to the untenable hypothesis that modern man is sexually repressed and, therefore, in need of sexual liberation, it comes as no surprise to find the Farrar's insisting that people are fearful of nakedness in much the same way that the slave is fearful of throwing off their chains and embracing freedom.

However, whilst the moral prohibitions of Judeo-Christian culture have undoubtedly shaped our thinking and behaviour, it's not in the straightforward and simplistic - not to mention entirely negative - manner that the Farrar's imagine. And couldn't it be that our fear of the naked body is as much due to an aversion for corpses and animality, as it is a sign of our repression ...?

Finally, the Farrar's argue that nakedness is a way of overcoming personal vanity and teaches those who would otherwise be seduced by "the appeal of splendid robes" to realise that "psychic effectiveness comes from within".

I have to admit, it's particularly disappointing to discover just how many witches seem to have a puritanical mistrust of fine clothes and expensive make-up. Do they not know the etymology of the term glamour? Historically, hasn't the witch always been a woman dressed in a striking fashion, with her pointed hat, full-length cloak, cat-skin gloves, and long-toed shoes? Hasn't she always understood the magic of colourful cosmetics and exotic perfumes?

So hostile are the Farrar's to the idea of wearing clothing during a ceremony that it is only with great reluctance that they make one small concession: menstruating women may, if they wish, keep their knickers on - providing they are of a plain cotton variety and nothing too frilly, colourful, or seductive. I'm afraid that as Nietzsche said of 19th-century feminism, we might say of 20th-century pagan witchcraft:

"There is an almost masculine stupidity in this movement [...] of which a real woman [...] would be ashamed from the very heart."

Today's witch should, in my opinion, revolt into style and dare to look splendid; not only delighting in her own appearance, but actively striking a blow against the drabness of the secular world with its blues and browns and sensible footwear. If she risks being thought a whore in her emerald-green stockings as she struts through town, better that than to be identified as just another office worker or shop assistant on her lunch break.

III. Closing Remarks

It's ironic, as Ronald Hutton points out, that in the ancient world pagan goddesses were most often associated with the city and with the arts and learning; i.e. with culture and society, not nature.

The goddess as Earth Mother is essentially a post-Romantic notion, created by poets like Swinburne and James Thomson. The latter, for example, published a verse in 1880 entitled 'The Naked Goddess' in which the heroine, Nature, comes to town only to be told by the local authorities to cover herself up immediately in either the habit of a nun, or the robes of a philosopher. Only the children appreciate her innocence and the beauty of her nakedness and, when she leaves the town, they return with her to the woods.

This is a nice story. But to make it into a kind of foundation myth, as neo-pagans seems to have done, is, I think, mistaken. Ultimately, whilst it may be magical to go wild in the country - swinging from the trees / naked in the breeze - so too is it a blessing to have a new pair of shoes and a warm place to shit.

Notes

* This and other papers from the series can be found in Vol. 1 of The Treadwell's Papers, by Stephen Alexander, (Blind Cupid Press, 2010).

Jane and Stewart Farrar, A Witches' Bible, (The Crowood Press, 2002), pp. 195-98.

Ronald Hutton, The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft, (Oxford University Press, 2001).

Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, trans. R. J. Hollingdale, (Penguin Books, 1990), VII. 239. I have slightly modified the line quoted here.

Readers interested in part one of this post on naked philosophers of the ancient world, should click here.

Readers interested in part two of this post on naked body culture in modern Germany, should click here.

Readers interested in part four of this post on streakers, should click here.