(John Hopkins University Press, 1997)

I.

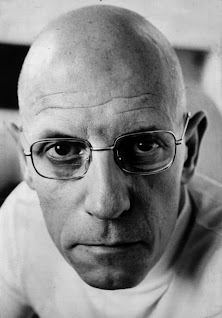

Vendredi ou les limbes du Pacifique (1967) is a novel by French writer Michel Tournier [a]. A philosophically-informed retelling of Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe (1719), it subverts the original narrative and, according to Deleuze, "traces a genesis of perversion" [b].

Crusoe's attempt to transform his little island into a regular, well-organised home-from-home - "like one of those great tidy cupboards" [8] full of lavender-scented linen - fails when he discovers, thanks to his relationship with Friday, that there are other ways of living than those valued within white European society.

Whether these ways are more natural, more authentic, or more vital, is, of course, open to debate. Personally, I'm not sure I buy into this anti-civilisation line any longer and doubt that there's all that much to learn from primitive peoples. And besides, I cannot gather at the drum any longer in good faith [c] and have no wish to wallow in the mire, roll in the damp warmth of my own excrement, or engage in savage acts of ritual atrocity. I'm not even interested in skinning a goat and making a wind harp from its dried entrails.

For just as you don't reach the body without organs and its plane of consistency by wildly destratifying, sometimes it's preferable to exercise caution and remain all too human, than become-other or become-animal just for the fun of it. As Deleuze and Guattari were always at pains to point out, staying organized, signified, subjected so that you may still respond to the dominant reality, is not the worst thing in the world [d].

Certain anarchists think we can do away with rules and regulations - just as certain gymnosophists think we can dispense with clothes. But as Crusoe discovers, keeping up appearances and forming habits of behaviour, are "sovereign remedies against the demoralizing effects of solitude" [76] - although later he abandons his old ways for a kind of solar pantheism.

II.

Friday appears about half-way through the novel and Crusoe's first instinct is to shoot him as he flees his Araucanian captors before they make a sacrifice of him, by chopping up his body and burning it.

Pursued by two men, Friday is running directly towards the spot in which Crusoe has been hiding and observing events on the beach, presenting the latter with a moral problem:

"If he shot down one of the pursuers he might rouse the whole tribe against him. On the other hand, if he shot the sacrificial victim it might be interpreted as a supernatural act, the intervention of an outraged divinity. He had to take one side or the other, being indifferent to both, and prudence counseled that he should support the stronger. He aimed at the breast of the fugitive, who was now very close ... [135].

Unfortunately, Tenn the dog decides to leap up and divert Crusoe's aim. And so Friday is saved and it was "the first of the pursuers who staggered and fell to the ground. The man behind him stopped, bent over the dying body, stared blankly for a moment at the trees, and finally turned and fled wildly back to his companions." [135]

And so, purely by accident, Crusoe ends up with a "naked and panic-stricken black man" [135] pressing his forehead to the ground and placing the foot of a "bearded and armed white man, clad in goatskin and a bonet of fur, accoutered with the trappings of three thousand years of Western civilization" [135] on his neck.

Now, no one in their right mind wants a slave: the responsibility of being a master is exhausting and quickly makes one ill-tempered and often cruel. It's bad enough having any kind of dependent - a child, an elderly parent, a pet cat, but a slave offering total submission is just too much trouble. And so, Crusoe makes a big mistake taking on Friday.

His second big mistake is trying to reform Friday and teach him all the white man's tricks; how to plough and sow, milk goats, make cheese, soft-boil eggs, trap vermin, dig ditches, wear clothes, etc. For Friday, with the slave's natural insolence, simply laughs at his his sober-minded mentor and undermines his authority on every occasion.

Ultimately, he ruins everything that it had taken Crusoe years to build - literally stopping the clocks and blowing everything sky-high with gunpowder. And it was all so predictable. Friday causes Crusoe grave concern from the off: "Not merely did he fail to fit harmoniously into the system, but, an alien presence, he even threatened to destroy it." [156]

But Crusoe simply can't bring himself to do what he needs to do in order to preserve the fragile victory of order over chaos that he had accomplised - not even after Friday fucks Speranza and produces mandrakes of his own from this illicit union. In fact, it's following this that Crusoe has a moment of biblical-inspired revelation:

"For the first time I asked myself if I had not sinned gravely against Charity in seeking by every means to compel Friday to submit to the laws of the cultivated island, since in doing so I proclaimed my preference, over my coloured brother, for the earth shaped by my own hands." [160]

It's this kind of Christian moral stupidity that undermines all mastery. Crusoe forces himself to conceal his vexation, swallow his pride, and henceforth learn to love Friday, forgiving him his ways even when they are profoundly shocking (such as his cruel indifference to the suffering of animals): "For the first time he questioned his white man's sensibilities" [163] and values.

Of course, there are moments when Crusoe pulls himself together and he feels nothing but rage and hatred as he thinks of "the ravages caused by Friday in the smooth functioning of the island, the ruined crops, the wasted stores, and scattered herds; the vermin that multiplied and prospered, the tools that were broken or mislaid" [164]. Friday even steals his tobacco.

Sometimes, Crusoe dreams of Friday's death; be it the result of natural causes, accident, or foul play. But at other times, the new Robinson adores Friday's physical beauty and delights in his nakedness; he observed with a passionate interest "Friday's every act and their effect upon himself, which seemed to lead toward an astonishing metamorphosis" [182].

Crusoe lets his hair grow into long tangled locks and, encouraged by Friday, he goes naked in the sun until his flesh takes on a deep, golden-copper colour. He has effectively gone native - or become-minoritarian as some might say [e].

That's certainly a goal for those who want it and Crusoe is clearly proud of the great change he has undergone via his relationship with Friday - "Under his influence [...] I have travelled the road of a long and painful metamorphosis" [210] - but, for me, it holds no appeal: I don't care if Monday's blue, I have no wish to become-Friday ...

III.

The

irony, of course, is that Friday jumps at the first opportunity to get

off the island and abandon Crusoe; he does everything he can to

ingratiate himself with the crew of the Whitebird so that he is

taken aboard and transported to England.

In other words, he knows where his best

interests lie; in the very civilisation that Crusoe rejects. Having said that, Tournier will later make it clear that he thinks this a grave mistake on Friday's part; a decision that will mark his downfall.

For, according to Tournier, unsmiling Europeans live in "glass cages of reserve, coldness, and self-containment" [f] and have an obsessive distrust of the flesh. Thus, a happy-go-lucky aeolian spirit like Friday will never find a home amongst such people ...

Notes

[a] The English edition of this work which I'll be referring to and quoting from throughout this post is simply entitled Friday, trans. Norman Denny, (John Hopkins University Press, 1997).

[b] Gilles Deleuze, letter to Jean Piel (27 August, 1966), in Letters and Other Texts, ed. David Lapoujade, trans. Ames Hodges, (Semiotext(e), 2020), p. 31. Deleuze will later describe Tournier's work as a great novel - a view shared by l'Académie française which awarded it the Grand Prix du roman in 1967.

[c] Despite his fascination (and, indeed, identification) with primitive cultures, D. H. Lawrence came precisely to this conclusion. In the essay 'Indians and an Englishman', he writes:

"The voice out of the far-off time was not for my ears. It's language was unknown to me. And I did not wish to know. [...] It was not for me, and I knew it. Nor had I any curiosity to understand. The soul is as old as the oldest day, and has its own hushed echoes, its own far-off tribal understandings sunk and incorporated. We do not need to live the past over again. Our darkest tissues are twisted in this old tribal experience, our warmest blood came out of the old tribal fire. And they vibrate still in answer, our blood, our tissue. But me, the conscious me, I have gone a long road since then. [...]

I don't want to live again the tribal mysteries my blood has lived long since. I don't want to know as I have known, in the tribal exclusiveness. [...] I know my derivation. I was born of no virgin, of no Holy Ghost. Ah no, these old men telling the tribal tale were my fathers. [...] But I stand on the far edge of their fire light [...] My way is my own, old red father; I can't cluster at the drum any more."

See Mornings in Mexico and Other Essays, ed. Virginia Crosswhite Hyde, (Cambridge University Press, 2009), pp. 119-120. Critics will doubtless point out that this model of human cultural evolution subscribed to by Lawrence - advancing from dark-skinned tribal society to white-skinned modernity - is certainly questionable (if not inherently racist).

[d] See Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massumi, (The Athlone Press, 1996), pp. 160-61.

[e] I have written about Crusoe's becoming-minoritarian via his relationship with Friday in an earlier post. See 'On the Sex Life of Robinson Crusoe 3: Becoming the Perverted Sun Angel' [click here].

[f] Michel Tournier, The Wind Spirit, trans. Arthur Goldhammer, (Collins, 1989), p. 185.

Later, in this same work, Tournier reveals that he had wanted to dedicate his novel "to all of France's immigrant workers, to those silent masses of Fridays shipped to Europe from the third world [...] on whom our society depends". And, just in case his political sympathies (and self-loathing) weren't already clear enough, he adds: "Our affluent society relies on these people; it has set its fat white buttocks down on their brown bodies and reduced them to absolute silence [...] They are a muzzled but vital population, a barely tolerated yet totally indispensable part of our society, and the only genuine proletariat that exists ..." Ibid., p. 197

For a counterview to this way of thinking, see Pascal Bruckner's The Tears of the White Man, trans. William R. Beer, (Free Press/Macmillan, 1986) and/or The Tyranny of Guilt: An Essay on Western Masochism, trans. Steven Rendell, (Princeton University Press, 2010). For my take on the latter text, click here.