I. The Death of Mrs Nickie Ben

For cat lovers, there's a very distressing scene early on in D. H. Lawrence's first novel, The White Peacock (1911). Cyril, the narrator of the story, and his sister, Lettie, are out walking in the woods and fields surrounding the local reservoir, when the latter suddenly lets out a cry:

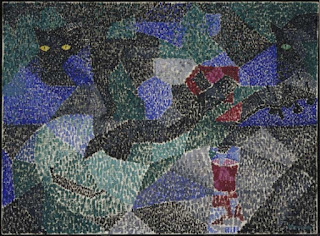

"On the bank before us lay a black cat, both hind-paws torn and bloody in a trap. It had no doubt been bounding forward after its prey when it was caught. It was gaunt and wild; no wonder it frightened the poor lapwings into cheeping hysteria. It glared at us fiercely, growling low."

Whilst Lettie stands looking on and lamenting the cruelty of man, Cyril takes action:

"I wrapped my cap and Lettie's scarf over my hands and bent to open the trap. The cat struck with her teeth, tearing the cloth convulsively. When it was free, it sprang away with one bound, and fell, panting, watching us."

This is no anonymous stray cat, however. This is a creature known to Cyril: Mrs Nickie Ben, who belongs at Strelley Mill, the home of his friend George Saxton. And so he wraps the poor creature in his jacket and carries her there.

Unfortunately, however, she is too badly injured to be saved, one of her paws having been broken: "We laid the poor brute on the rug, and gave it warm milk. It drank very little, being too feeble." Even the presence of her mate, another fine-looking black cat, doesn't rouse her. And besides, he seems indifferent to her suffering:

"Mr Nickie Benn looked, shrugged his sleek shoulders, and walked away with high steps. There was a general feminine outcry on masculine callousness."

George decides to put the cat out of her misery. His preferred method of doing so - and the quickest - is to "'swing her round and knock her head against the wall'", but Lettie protests. And so he decides to drown her: "We watched him morbidly, as he took a length of twine and fastened a noose round the animal's neck [...]"

George smiles as he walks to the garden pond and then drops "the poor writhing cat into the water, saying 'Goodbye, Mrs Nickie Ben'". Vile deed done, he hauls the cat out, amused by the grotesque character of the corpse.

He then buries her in a shallow grave, commenting to Cyril and Lettie: "'I had to drown her, out of mercy [...] If the poor old cat had made a prettier corpse, you'd have thrown violets on her.'"

He then buries her in a shallow grave, commenting to Cyril and Lettie: "'I had to drown her, out of mercy [...] If the poor old cat had made a prettier corpse, you'd have thrown violets on her.'"

II. Lady Chatterley's Pussy

Interestingly, there's another black cat who also comes to a sticky end in Lawrence's final novel. In chapter six of Lady Chatterley's Lover (1928), Connie goes for a walk in the woods - as she often did on one of her bad days. The sound of a gun shot nearby startles her out of her vague indifference to her surroundings.

Going to investigate, she hears the sound of a man's voice, followed by the sound of a child sobbing. The thought that someone might be ill-treating the latter rouses Connie's anger: "She strode surging down the wet drive, her sullen resentment uppermost. She felt just prepared to make a scene."

It was the keeper - Mellors - and a little girl, wearing a purple coat and moleskin cap. The latter was crying, to the irritation of the former: "'Ah, shut it up, tha false little bitch!' came the man's angry voice", though, not surprisingly, this only made the child wail louder.

Connie marches up to them, with her dark blue eyes blazing, demanding to know what's going on. He salutes her ladyship, but with a faint smile all too like a sneer on his face and he tells her - in broad vernacular - that she'd best ask the child, not him, what the problem is. And so Connie turns to the "ruddy, black-haired thing of nine or ten", saying: "'What' is it, dear?'" with conventionalised sweetness of tone.

The child, however, continues to sob; violently, but also self-consciously. In the end, Connie bribes her with a sixpence. This placates the brat and enables her to speak: "'It's the - it's the - pussy!'"

It turns out that the keeper - her father - has shot a poaching cat: a big black cat, that now lies stretched out and bleeding amongst the bramble. Connie is repulsed by the sight and she turns on her soon-to-be lover and tells him it's no wonder the child was upset.

She tries to further reassure the child (whilst secretly disliking the spoilt, false little female), before escorting her home to her grandmother, leaving Mellors to dispose of the dead moggie in a manner undisclosed.

III.

Whether these two scenes reveal anything of import about Lawrence's views on black cats, cruelty, and sexual politics is debatable.

But what they do demonstrate is that there's more than one way to kill a cat and that underlying all of Lawrence's fiction is not so much a naive or innocent vitalism, but a fascination with violence and death and the part these things play in life as a general economy of the whole. In other words, Lawrence's philosophy is a form of tragic pessimism - but a pessimism of strength.

She tries to further reassure the child (whilst secretly disliking the spoilt, false little female), before escorting her home to her grandmother, leaving Mellors to dispose of the dead moggie in a manner undisclosed.

III.

Whether these two scenes reveal anything of import about Lawrence's views on black cats, cruelty, and sexual politics is debatable.

But what they do demonstrate is that there's more than one way to kill a cat and that underlying all of Lawrence's fiction is not so much a naive or innocent vitalism, but a fascination with violence and death and the part these things play in life as a general economy of the whole. In other words, Lawrence's philosophy is a form of tragic pessimism - but a pessimism of strength.

See:

D. H. Lawrence, The White Peacock, ed. Andrew Robertson, (Cambridge University Press, 1983), pp. 12-13.

D. H. Lawrence, Lady Chatterley's Lover, ed. Michael Squires, (Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 58-59.