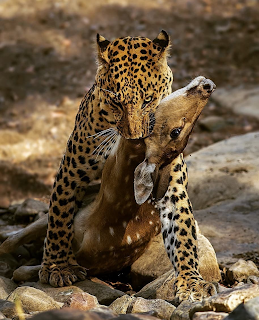

Detail from 'The Struggle' (1992)

Garry Shead: D. H. Lawrence Series

I.

In his Introduction to the Cambridge Edition of Kangaroo, Bruce Steele argues that whilst the novel is "in many respects thinly disguised autobiography", uncritical emphasis on this pervasive element has led to the mistaken assumption that the character Richard Lovatt Somers is identical with Lawrence as narrator, even though "Lawrence as narrator [...] is often sharply distinct from his character Somers and frequently critical of him and his views" [a].

And that's true - but

doesn't go far enough. For I would not only challenge the ridiculous idea

that Somers is identical with the narrator, but interrogate also the

belief that the narrator can be identified with an Author who resides

outside (and above) the text and in whose person is found the very

origin of the work and its ultimate truth.

In this post, therefore, I'm concerned only with Richard Somers and not interested in making any attempt to tie Kangaroo

as a work of fiction to Lawrence's own memories, foreign travels,

political views, or sexual fantasies. As Deleuze says, creative writing

that is overly reliant upon autobiography is not only often bad writing,

but dead writing; for literature dies from an excess of authorial input just as it does from an overdose of reality.

II.

Richard Somers is a queer fish: a small, foreign-looking, slightly comical figure, with a pale face, dark beard, and an absent air of self-possession that spoke not only of his (in)difference, but innate superiority and sensitivity (as indicated by his Italian suit and brown shoes).

His middle name, Lovatt, suggests either something wolfish about his nature, or something rotten; either way, he doesn't like to be cheated by taxi drivers - but then, who does? Nor does he find humorous house names very amusing - but then ...

To be fair, Somers could be charming - when he wanted - but mostly he liked to keep himself to himself and not to "speak one single

word to any single body" [19] - except Harriett, his wife, "whom he snapped at hard

enough" [19]. The thing he hates most of all is "promiscuous mixing in" [36] and informality.

Unfortunately, Somers can't help feeling himself in touch with (and responsive to) others due to the fact he possessed "the power of intuitive communication" [37]. However, despite this, Somers "would never be pals with any man" [38].

Somers was a writer of poems and essays, with an income of £400 a year (i.e., about twice the average wage in 1922). So, whilst not rich, he was able to globe-trot, admiring the local flora whilst despising the natives and forever asking himsef why he had ever bothered to leave England: Somers "wandered disconsolate through the streets of Sydney" [20], longing to be back in London.

Still, if the city disappoints, the Australian bush makes a tremendous impression upon him: "Richard L. had never quite got over that glimpse of terror in the Westralian bush" [15]. He was sure a menacing spirit of place had been watching him as he walked amongst the ghostly pale trees. Watching - and waiting to grab him. For as a poet, Somers felt himself "entitled to all kinds of emotions and sensations which an ordinary man would have repudiated" [14].

But of course, as the narrator of Kangaroo notes: "It is always a question, whether there is any sense in taking notice of a poet's fine feelings." [15] Or indeed, his prejudices - of which Somers has many; mostly rooted in his snobbishness, such as his dismissal of Australians "with their aggressive familiarity" [21] as barbarians, lacking in class and culture. For Somers, there has to be rule - otherwise there's just a form of irresponsible anarchy and bullying.

"Poor Richard Lovatt wearied himself to death struggling with the problem of himself, and calling it Australia." [28] That's an interesting remark. But what is Somers's problem? I'm not sure - perhaps we'll find out by the end of this character study ... And maybe we'll find out too what lesson it is that Somers thinks the world has got to learn [31] - or why it is he seems so fascinated by the legs of young men in bathing suits on the beach [27].

But maybe not: maybe Somers will always remain something of an enigma: for it was "difficult to locate any definite Somers, any one individual [...] The man himself seemed lost in the bright aura of his rapid consciousness" [38]. Somers, we might say, is mercurial and light-footed. He's also a reckless chess player; "very careless of his defence" [39], which is odd for someone so guarded in other respects.

For a man who, by his own admission, never takes any part in politics, Somers does seem to hold a number of very definite political views; as might be expected of a writer of essays on social and political topics, such as the future of democracy or the fate of capitalism. And his views might best be described as national socialist in character (all that talk of blood and soil), or as a kind of demonic radicalism (all that talk of dark everlasting gods).

Somers also fancies that it's his "own high destiny" [92] to be a leader of men one day and to make some kind of opening in the world. Though, push comes to shove, he can't commit to any cause, party, or movement. Nor even to Benjamin ('Kangaroo') Cooley. Something always stops him; "as if an invisible hand were upon him" [106].

Thus, whilst Somers might crave living fellowship with others, he does not want affection, love, nor comradeship. For living fellowship, it turns out, is a synonym for the mystery of lordship. That is to say, the thing which the dark races still know:

"The mystery of innate, natural, sacred priority [...] which democracy and equality try to deny and obliterate [...] the mystic recognition of difference and innate priority, the joy of obedience and the sacred responsibility of authority" [107] [b].

At other times, however, Somers rejects the human world entirely - and I think I like him best at such moments; when he is filled with cold fury and contempt for mankind and cares only for the dark cold sea, dreaming (in what is perhaps my favourite section of the novel) of becoming-fish:

"To have oneself exultingly ice-cold, not one spark of this wretched warm flesh left, and to have all the terrific, ice energy of a fish. To surge with that cold exultance and passion of a sea thing! [...] No more cloying warmth. No more of this horrible stuffy heat of human beings. To be an isolated swift fish in the big seas, that are bigger than the earth; fierce with cold, cold life, in the watery twilight before sympathy was created to clog us.

They were his feelings now. Mankind? Ha, he turned his face to the centre of the seas, away from any land. The noise of waters, and dumbness like a fish. The cold, lovely silence, before crying and calling were invented. His tongue felt heavy in his mouth, as if it had relapsed away from speech altogether.

He did not care a straw what [...] anybody said or felt, even himself. He had no feelings, and speech had gone out of him. He wanted to be cold, cold, and alone like a single fish, with no feeling in his heart at all except a certain icy exultance and wild, fish-like rapacity. [...] Who sets a limit to what a man is. Man is also a fierce and fish-cold devil, in his hour, filled with cold fury of desire to get away from the cloy of human life altogether, not into death, but into that icily self-sufficient vigour of a fish." [125]

As Zarathustra might say: Man needs what is most piscean in him for what is best in him ... [c]

This series of notes for a character study of R. L. Somers is continued in part two of this post: click

here.

Notes

[a] Bruce Steele, Introduction to D. H. Lawrence's Kangaroo, ed. Bruce Steele, (Cambridge University Press, 1994), p. xxiii. All future page references to this work will be given directly in the post.

[b] This is, of course, a fantasy of the reactionary imagination and one which I have discussed recently on Torpedo the Ark in terms of natural aristocracy: click here. I also discuss the politics of this passage in chapter 5 of Outside the Gate, (Blind Cupid Press, 2010), see pp. 100-126, and will comment further on Somers's politico-theological speculations in part two of this post.

[c] I'm paraphrasing a famous line written by Nietzsche in Thus Spoke Zarathustra - see the section entitled 'The Convalescent'.